I temper my temper with laughter. Hurriedly washing dishes and breaking a glass, I swing a fist at the air for the extra work of cleaning it up, while a volley of profanity bursts like bad poetry from my lips. Turning, I glimpse my face in the hallway mirror, and the red of my fury cedes place to the red of my shame. Feeling my rational judgment stare down my charade, squirming under my own rebuke, I lighten the moment with a laugh. Thus my tantrums do not so much release my anger as embarrass me into being more patient. Could the cantankerous world likewise hold a mirror up to war, humanity would be shamed into peace.

Emotions

During the fireworks finale on the Fourth of July, when the slow parade of booms accelerates to a brief orgasm of explosions, people swell in pride for their country and clap and yell and madly wave flags. Observing this sudden groundburst of nationalism, I wonder what intrinsic link is there between fireworks and flag waving? I miss a step somewhere in the syllogism: explosions are exciting, therefore America is great. Gunpowder and oxidized metal rouse our adrenaline, but Uncle Sam takes credit. The fireworks sow, patriotism reaps. If it were New Year's Eve, our resolutions rather than our patriotism would inherit the force of our festivity. If we were Hitler Youth at our first parade, our awe would prove the glory of the Führer.

At weddings, when flutes and violins make women's cheeks wet, I often roll my eyes because crying at weddings seems mawkish and predictable, and I could never give in to such a routine. But if I call myself a thinker, I ought instead to envy their tears. While those mascaraed ladies meditate on youth and beauty, loneliness and love, time and till death do us part, I sit stiffly and self-consciously in my pew, thinking not of the human condition but of my own superiority. Nothing is shallower than pride.

If women cry more than men, as they are stereotyped, they are the deeper sex, plumbing life's magnificent sorrow while the sports-watching, business-traveling, engine-fixing men live practically, that is, practically don't live.

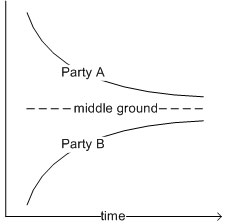

Negotiators—whether politicians or homebuyers—begin with bold concessions which rapidly shrink the gulf between opposing sides. But like curves approaching an asymptote in geometry, as they near an agreement they level off and struggle to bridge the final, though trivial, gap. The effect of their ongoing quarreling is that, by the end, their motivating goal is not so much to strike a deal or make a sale as to make the other side yield, on no matter how minor a point. The fact of winning a concession matters more than the concession's substance. Not who yields most, but who yields last, appears to lose. The negotiation grows more bitter, the less remains at stake.

Negotiators—whether politicians or homebuyers—begin with bold concessions which rapidly shrink the gulf between opposing sides. But like curves approaching an asymptote in geometry, as they near an agreement they level off and struggle to bridge the final, though trivial, gap. The effect of their ongoing quarreling is that, by the end, their motivating goal is not so much to strike a deal or make a sale as to make the other side yield, on no matter how minor a point. The fact of winning a concession matters more than the concession's substance. Not who yields most, but who yields last, appears to lose. The negotiation grows more bitter, the less remains at stake.

I am a better reader now than when I was in graduate school, because I read with less enthusiasm. I can stay with a book from cover to cover, whereas in graduate school I could scarcely finish anything, because I wanted to read everything. Ten pages in, I was craving the next book. My patience was insufficient for novels, so I mostly read poems and essays. To visit libraries paralyzed me with my options. I sampled tables of contents endlessly, but an excess of hunger prevented me from eating.

I knew a friend in college who behaved similarly toward people at gatherings. Spotting you from across the room, he would curtail his conversation and weave through crowds to greet you, but as he shook your hand, his eyes were already scanning for the next friend he craved talking to. His hand and eyes, his having and wanting, were always out of sync. He liked so many people that he scarcely knew anyone beyond hello.

Too much desire is self-defeating, wildly overrunning the thing it wants. Passions need a pinch of apathy to slow them down to the pace of enjoyment.

Often the shock of a shooting spree is that we never guessed the inner magnitude of the gunman's despair. Meeting neighbors in public, he would shake their hands and talk of sports or politics. How could such a maelstrom be swirling beneath so placid a surface?

A desperate man moves through society like a wave through deep water, its power hidden till, suddenly rising, it bursts against the rocks.

For the young, music is an intimation of life. Each sonata or concerto cracks, but does not fully open, the door to worlds not yet experienced. The violin, singing of unknown desires, stirs desire. The cymbals' crescendo resounds with heights of elation not yet relished. The bass drum booms a cryptic proclamation of great events—happening where? For the old, music is a memoir of life. The buried strata of past experience, loosened by the mysterious psychoanalysis of sound, erupt into consciousness. Sorrows and joys which played singly through time now harmonize into a grand symphonic impression of the tremendousness of living. Must not the brittle self shatter to have been poured so full of experiences?

In a concert hall, the girl in bloom closes her eyes and imagines all she may be, while beside her the wrinkled widow closes her eyes and remembers all she has been.

Young writers are often guilty of contriving passion. They begin their work in earnest, but then they overstep the limits of their real feelings, adorning their hard-won experiences with borrowed ideas in the hope of enhancing the impact, yet actually diminishing it. Nevertheless, this youthful erring toward artifice and overextension is rooted in genuine ardor. Because young writers feel so impassioned, they try too hard to impassion their readers. Should not the reader then forgive this falseness born of authenticity?

Mr. Stanley’s Aphorisms and Paradoxes are outstanding examples of the long-form aphorism... inevitably studded with discrete individual aphorisms that could easily stand on their own.

Mr. Stanley’s Aphorisms and Paradoxes are outstanding examples of the long-form aphorism... inevitably studded with discrete individual aphorisms that could easily stand on their own.

-James Geary, author of The World in a Phrase: A Brief History of the Aphorism

As Seen In: